History

Global Health: A Brief Essay on the University of Minnesota’s 150 Year Commitment

Written by Dean John Finnegan

Beginnings

On a beautiful Minnesota winter day (blue sky, deep snow cover, well below-zero) just before Christmas, 1869, the University of Minnesota inaugurated its first official president, Dr. William Watts Folwell. The new President spoke in “Old Main” on what is today the University’s Twin Cities “East Bank” campus. He painted an aspirational vision for the fledgling land grant institution. It included the words “public health.”

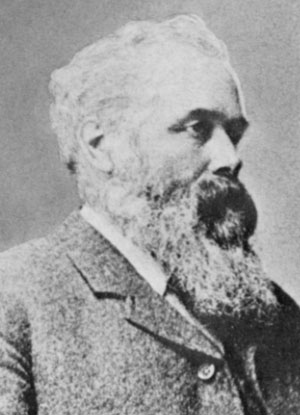

“The time is not distant when a department of public health will be established in all universities…” he told the assembled. That was the beginning of the University’s commitment public health and global health. Within five years, Folwell recruited Red Wing physician Dr. Charles N. Hewitt to the faculty, naming him the first “Non-resident Professor of Public Health” in 1873. His was likely the first academic appointment establishing the burgeoning field of public health in the United States (Myers, 1966, p. 34). Both Folwell and Hewitt viewed public health as a synergistic mix of basic science, applied research, education, professional training, and community practice, astride a platform of systems propelled by public policy. Hewitt was the architect of Minnesota’s first public health system, putting the state in the company of California, Massachusetts and Virginia and far ahead of the rest of the nation. On Hewitt’s death in 1910, Folwell would memorialize him as Minnesota’s “Apostle of Public Health.”

“His lectures on public health,” Folwell wrote, “were probably the first delivered in an American college.”

As a surgeon in the bloody US Civil War, Hewitt forged his understanding of newly emerging disease models. He knew of the early work of Louis Pasteur and the emerging biology of “germ theory.” During the war, Hewitt was General U.S. Grant’s “go to” physician for cleaning up Union camps and reducing their terrifyingly high casualty rates due to bad water, bad sanitation, and gangrene from filthy surgeries. After joining the University, Hewitt turned these ideas into Minnesota’s first effort to educate college students in health and hygiene, and health professionals too. Coincidentally, in the year following his appointment (1874), the University welcomed its very first international students from Denmark and Canada, and also began weaving foreign languages into its curricula.

In the spring of 1890, Hewitt travelled to Paris where he studied under Pasteur at the Institute that still bears his name. Then 67 years-old, Pasteur was a legendary microbiologist, biologist and chemist who had saved tens of thousands of lives through his vaccination research. Hewitt wanted Pasteur’s guidance especially in his scientific methods. He also met the physician and bacteriologist Robert H. Koch who had identified the causal agents of cholera, anthrax and tuberculosis.

Hewitt understood, promoted and practiced public health in part because he recognized its global scale and scope. Disease and illness, especially infectious and communicable, recognized no boundaries whether of nation-states or socioeconomic class. By the last decades of the Nineteenth Century, immigration was increasing around the world and into the United States. Million-plus populated cities had emerged all over the planet. Public health had become global health.

The Twentieth Century

The University’s interest in public and global health grew in the following century as world immigration increased, and the planet’s first World War festered then exploded in Europe. In the period leading up to the war, the US experienced the most intense immigration in its history, driven by the collapsing political situation across Europe. Travel technology, wired and wireless communication, and the growing interdependence of “global” markets in goods and commodities were among the powerful forces driving it.

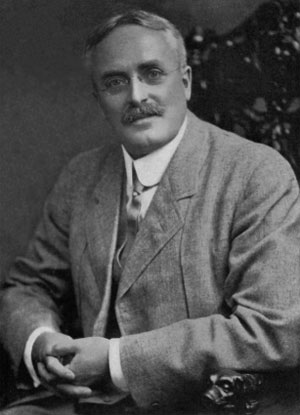

At the University of Minnesota, Frank S. Wesbrook, MD, had been appointed dean of the medical college in 1906, a position he would hold until 1913 on the eve of World War I. Like Hewitt before him, Wesbrook understood the increasing globalization of health. Born in Canada and educated in England and Germany, he became a bacteriologist and pathologist with a focus on public health. For a time, he practiced as the Minnesota’s “State Bacteriologist,” until he accepted appointment as the Medical College’s first full-time dean. Wesbrook led the reorganization of the medical curriculum to include some education of physicians in public health. It was still a “hard sell” to most of his faculty colleagues. As immigration to the US and Minnesota grew, he recognized that skills in both areas were required of physicians. He also persuaded the University to establish a new Institute of Public Health and Pathology on the Minneapolis campus and to put up a new building to house it.

Meanwhile, the University’s international profile was rising. While students from other countries, mainly Canada and Europe, had enrolled at Minnesota since 1874, the first students from China arrived in 1914 as World War I began. Minnesota was increasingly the choice of students from other countries due in part to its agricultural, engineering, education and health sciences presence, all areas critical to nation-building and recovery post-war.

Wesbrook resigned from the University in 1913 to return to Canada where he had been appointed President of the University of British Columbia. His goal? To establish a new medical school and school of public health in the province. Establishing a school of public health at Minnesota would not happen until 1944, but in 1922, the Medical College had transformed Wesbrook’s Public Health Institute into the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine. He had laid a solid foundation with a global spin.

Post World War II

World War II and its aftermath propelled public and global health truly planet-wide. The US had been a leader in establishing schools of public health post World War I, but mainly by private universities and very few publics. The US position as a major world leader after World War II led to major investments in global health, as a tool of nation-building and recovery. To take up that mantle, the country was putting aside traditional isolationist attitudes, part of its political culture since pre-colonial days. By the close of the war, plans were already developing to bring nations together formally in ongoing contact and collaboration. It was tried at the close of World War I as the League of Nations, but American isolationism factored importantly in its failure. The United Nations promised to be different in part because of bipartisan recognition in the nation’s politics that world wars must never recur, an aspiration the more critical in the presence of nuclear weapons. All was becoming “global,” especially recovery through economic development, health, and education. A major player in helping to establish this new global infrastructure including such elements as the WHO, was former Minnesota Governor and Republican Party member, Harold E. Stassen.

The war and its aftermath had a major effect in accelerating research and discovery within what we call today STEM, but also medicine, public health and related disciplines and professions. The establishment of the US Federal Government infrastructure coming out of the war provided a new, powerful platform for research, learning and community engagement driving US higher education into world class ranking and impact.

As the US assumed its leadership role, an increasing number of public university schools of public health appeared with a growing international emphasis. Minnesota’s was among the second wave of these schools. Dr. Gaylord Anderson, MD, DrPH, had become Minnesota’s founding dean of its new school of public health based on bequests from the estates of Drs. Charles and William Mayo. The new SPH would also continue to serve as the Medical School’s Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine for some years afterward.

Anderson had quite a bit of public health experience in the military during the war. He marshalled it into a constructive approach to global health. Following the Korean War armistice in 1953, for example, the Federal Government approached the University of Minnesota with funding to mount an educational aid project. The goal was assisting South Korea in re-establishing its capacity to educate physicians and other health professionals, including public health. Anderson surveyed the situation in Seoul, reporting to Federal and UMN leadership that it could work. Dozens of South Korean faculty studied at Minnesota over the years until 1961, to restore and grow their capacity in health research and training. University of Minnesota faculty also worked directly with colleagues at Seoul National University during the period.

The sense of “global” with respect to the school’s vision of, and engagement in public health drove the work of major Minnesota scholars and researchers during and post-war. For example, the physiologist Ancel Keys and his colleagues began seminal observational work in the famous Seven Countries Study looking at cardiovascular disease as a global phenomenon yet with enormous national differences in associated behaviors and culture. In doing so, Keys built an international network of colleagues and institutions focused on the world’s number one cause of premature mortality.

Such global networks of colleagues and institutions have certainly accelerated in the digital world. Researcher James Neaton, Professor and Director of the Coordinating Center for Biometric Research is a central member of a vast global clinical trials network that has conducted research in AIDS/HIV drugs, vaccines, and more.

Regents Professor Michael Osterholm directs the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) which relies on a worldwide network of individual and institutional news sources to track the threats of infectious disease outbreaks and public policy challenges in public health preparedness.

In the digital world, the School of Public Health collaborates extensively with other UMN colleges and universities and institutions around the world in addressing Emerging Pandemic Threats as part of a USAID network of global health.

Conclusion

Many have written that public health is about collective action for change in the conditions that challenge health in the first place. Others have noted that global health itself is about changing the conditions that produce inequity in health and thwart health improvement. It’s easy to see why global and public health have become essentially interchangeable terms – although a few would disagree vehemently. My personal feeling is that “global health” is more deeply and explicitly anchored in the language and concepts of human rights. While many in the US are fully comfortable with that frame, our dysfunctional partisan politics often stumbles over it. Whatever the nuances, we have entered a time historically when national isolationism is essentially impossible. In the world of global/public health, recognizing that is a step toward a better world – for everyone.

Sources:

University of Minnesota (1870).The Addresses at the Inauguration of William W. Folwell as President of the University of Minnesota, Wednesday, December 22, 1869. Minneapolis, MN: Tribune Printing Co.

William Watts Folwell (1914). Biographical Memorial of Dr. Charles N. Hewitt. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, Vol XV, pp. 669-686.

Thomas E. Keys (1940). The Medical Books of Dr. Charles N. Hewitt (PDF). St Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

Jay Arthur Myers (1968). Masters of Medicine: An Historical Sketch of the College of Medical Sciences, University of Minnesota, 1888-1966. St Louis, Missouri: Warren H. Green Co.