It’s no longer debatable: gun violence is a problem.

While we are shocked by high-profile mass shootings fueled by hate and terrorism, data shows that these account for less than one percent of violence using firearms. Day-to-day, the majority of firearm deaths are suicides, followed by homicides.

While we are shocked by high-profile mass shootings fueled by hate and terrorism, data shows that these account for less than one percent of violence using firearms. Day-to-day, the majority of firearm deaths are suicides, followed by homicides.

So how do we begin to tackle this enormous issue, wrapped up in politics and emotion? Many experts agree that the way to reduce firearm-related injury and death requires a public health approach, which has been effective in previous challenges like vehicle safety, and tobacco and alcohol use.

A public health approach focuses on what really matters: keeping citizens safe and healthy. “The public health approach is about preventing people from being killed or hurt by guns,” says John Finnegan, School of Public Health dean and professor. “We look at the problem through multiple interventions — education, technology, and policy — as many paths leading to a solution. I know that some people are deeply afraid that this includes taking away people’s guns, but that’s not what we’re about. For us, it’s about realistic ways to reduce the carnage.”

“The public health point of view is all about making what is healthiest for the community and the individual easy,” says Nancy Nord Bence, executive director of gun violence prevention nonprofit Protect Minnesota. “Instead of focusing on each particular shooter, public health looks at the larger population and asks, ‘How can we make gun ownership safer?’”

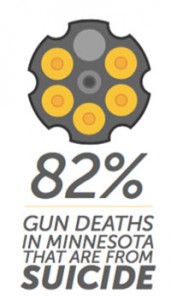

Self-inflicted Injury

The number one cause of death by guns is self-inflicted. Nationwide, 60 percent of gun deaths are from suicides, that number rises to 82 percent in Minnesota and is the eighth leading cause of death in our state.

“As a means of suicide, firearms are very, sadly successful,” says Finnegan.

While suicide is up among all age groups, suicide prevention is often only geared toward youth. Youth suicides have increased 10 percent since 2000, but among working-age adults, suicide is up by 44 percent. Among the elderly, it’s up 30 percent. “We are preventing suicides, but we need to prevent more,” says Jon Roesler, MS ’87, head of the Minnesota Department of Health’s Violent Data Reporting System. “We need to target all age groups, not just youth, with suicide prevention methods.”

While suicide is up among all age groups, suicide prevention is often only geared toward youth. Youth suicides have increased 10 percent since 2000, but among working-age adults, suicide is up by 44 percent. Among the elderly, it’s up 30 percent. “We are preventing suicides, but we need to prevent more,” says Jon Roesler, MS ’87, head of the Minnesota Department of Health’s Violent Data Reporting System. “We need to target all age groups, not just youth, with suicide prevention methods.”

Many argue that most suicides could be prevented by a very simple act. “If you feel someone may be suicidal, the best thing you can do is make sure they don’t have guns in the house, even if [guns are removed] just for a short while” says David Hemenway, professor at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University and a national expert on gun violence, who spoke at the School of Public Health in June 2016 as part of the school’s Gaylord Anderson Memorial Lecture.

“Suicide is a split-second impulse decision and every step we can put in a person’s way, the higher the likelihood that they will never die of suicide,” says Nord Bence.

“[Removing guns from the reach of a suicidal person] is like taking away someone’s car keys who is drunk,” says SPH Professor and injury prevention expert Bruce Alexander.

But the connection between guns and suicide is often not made. SPH Professor Sue Gerberich, injury epidemiologist and co-director of the Center for Violence Prevention and Control, says there is pressure on the press not to report gun-related suicides for fear of copycats. Family may also be reluctant to talk about a loved one’s suicide.

Homicides

In 2015, there were 65 homicides in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Of those, 49 involved a gun.

“The majority of homicides are between people that are known to each other,” says Alexander. “Mass shootings and hate crimes account for a small fraction of gun violence.”

Nord Bence argues that homicides have been portrayed as a “black-on-black” problem, but gun violence cannot be ignored in white communities. “84 percent of white people killed in homicides are killed by other white people. Add that to the fact that white people kill themselves much more frequently than black people do, and you can see that gun violence is really, statistically, a white problem in Minnesota.”

Nord Bence argues that homicides have been portrayed as a “black-on-black” problem, but gun violence cannot be ignored in white communities. “84 percent of white people killed in homicides are killed by other white people. Add that to the fact that white people kill themselves much more frequently than black people do, and you can see that gun violence is really, statistically, a white problem in Minnesota.”

Communities around the United States are experimenting with various methods to prevent homicides. The most successful model to date is called Cure Violence (CV), which creates individual and community-level change in communities where young people carry a gun.

The CV model focuses on high-risk individuals, but also simultaneously instills conflict resolution and anti-violence norms throughout the community. The program, which includes outreach workers and violence interrupters, has been implemented in Chicago, Baltimore, Phoenix, Brooklyn, and Pittsburgh.

While the program has had mixed success and further work is needed, “programs like this have shown us that using public health methods can have an impact on hate and can work to change norms,” says Finnegan. “Every act of violence prevented could be a life saved.”

Painting the Picture

In 1995, then-Minnesota Governor Arne Carlson declared gun violence a public health issue. At the time, Minneapolis was dubbed “Murderapolis” and experienced 100 homicides in one year, which is about how many homicides the entire state has now, with a 20 percent larger population.

To understand the impact of violence on the health care system, Twin Cities hospitals began coding injury-related deaths to identify if the cause was a motor vehicle accident, a fall, self-inflicted, a gunshot wound, or something else.

“We started to see the role of firearms in injury-related deaths and we started to see the real story of gun violence through this data,” says Roesler.

But to reduce the number of violent deaths nationwide, there was a need for more comprehensive data. In 2002, the CDC provided funding for the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), a state-based surveillance system that gathers information about violent deaths. It does not fund research on the data, only the data collection itself. NVDRS links detailed information from death certificates, police reports, coroner reports, and crime labs in an effort to find out why the deaths occurred. The information is added to an anonymous national database.

Slowly states were added to the NVDRS, and, in 2015, Minnesota joined the system and the Minnesota Violent Death Reporting System (MN-VDRS) was created and housed within the Minnesota Department of Health’s Injury and Violence Prevention Unit.

Headed by Roesler, MN-VDRS goes a step beyond what’s available on the death certificate. For example, the death certificate may say “death by firearm,” but Roesler’s team will identify the caliber of the gun and who made the fatal shot.

Roesler says Minnesota has approximately 40,000 deaths per year, with about 1,000 of those meeting the NVDRS criteria, meaning the death is considered violent. Of those 1,000 deaths, 70 percent are suicides, 20 percent are homicides, and the rest are undetermined, as of now.

“To prevent gun violence, we need to have better surveillance to fully understand the big picture,” says Roesler. “NVDRS came in part because our society was concerned about gun violence, and from our data, for example, we can see we’re becoming more suicidal in Minnesota.” We must now, Roesler says, use the data to add vital information to policy debates.

The Next Generation

Because of complicated nature of gun violence research, many current public health practitioners haven’t had the opportunity to study gun violence (see “Where is the Research?” sidebar). This creates opportunities for current public health students to explore these issues and potentially lead future interventions.

In spring 2016, SPH student group Active Response Coalition for Public Health hosted a panel to talk about gun violence titled, “Gun Violence and Public Health: The Challenges of Prevention and Promotion.” Organized by students, the panel featured high profile community members as well as a keynote from Minnesota Congressman Keith Ellison.

“I was so impressed that the students wanted to take on this tough issue,” says Finnegan, who moderated the discussion. “The event was the first of many gun violence discussions we want to have here at SPH and they started a really important conversation.”

In addition to events like these, students take courses that dive into injury prevention and gun violence, as well as health disparities. “These students have seen the effects of gun violence and they want to change its course,” says Finnegan. “It’s these students, who are well-suited through their education and their willingness to save lives, that are well-positioned to solve this crisis for our country.”

Where is the Research?

While the United States struggles to be proactive in curbing gun violence, research on the problem has been stymied for the past 20 years by a so-called “funding ban” on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to study gun violence.

In 1996, Arkansas Representative Jay Dickey, with support and lobbying from the National Rifle Association, inserted a rider into a federal spending bill that stipulated that no CDC funds “may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” The bill passed, rider intact.

Congress also went on to cut $2.6 million from the CDC’s overall budget — the exact amount the CDC had invested in firearm injury research.

Together, these actions were enough to discourage gun violence research.

“Unfortunately, there are economics that drive research and you go where the work and funding is,” says SPH Associate Professor Toben Nelson, who began his career in injury prevention and now studies alcohol and obesity.

“Gun violence is a topic of interest for me, but it became clear early in my career that gun violence was not going to get a lot of support from federal agencies,” says Nelson. “There was money for injury prevention more broadly, but any time guns were involved in the mix, there was hesitation from funders and fellow researchers to collaborate.”

After the 2012 shooting of 20 schoolchildren and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary, President Obama issued an executive order instructing the CDC to “conduct or sponsor research into the causes of gun violence and the ways to prevent it.” Since then, the NIH has funded three studies related to firearm injury and the National Institute of Justice has awarded $2 million in funding for firearms-related research.

But the vague language of Dickey’s rider remains in place, and the CDC is nervous to study gun violence. Especially as funding requests continue to be thwarted. President Obama asked for $10 million in funding for the CDC’s gun violence research, and in both 2012 and 2013, the request was blocked by Congress.

“Congress is ignoring a major public health issue,” says SPH Professor Bruce Alexander. “Data tells us about gun-related deaths, but what about injuries from firearms that don’t result in death? We have no basic information to even start a reasonable conversation leading to wiser policies. Instead, the issue is just polarized.”

While research is stalled, Jon Roesler, MS ’87, head of the Minnesota Department of Health’s Violent Data Reporting System, says public health can still play a role. “As the congressional ban still prohibits the CDC from funding research on gun violence, there is clearly a role for public health surveillance to help us understand trends to inform policy.”

What You Can Do

You may feel powerless in the face of today’s gun violence epidemic. But there are steps you can take to help make a difference.

Prevent Gun-Related Incidents and Deaths

If you own a gun, lock it up and store ammo away from the gun.

The majority of unintentional gun deaths happen in the home. It’s well-known that a gun in your home is more likely to kill or hurt someone in your own family than an intruder. “We have to change the idea that owning a gun makes you safer,” says Nancy Nord Bence, executive director of Protect Minnesota.

When it comes to protecting your children, Nord Bence has an easy, but potentially awkward recommendation. “If your child is going to a friend’s house, ask the parent if there is an unlocked gun in the house,” she says. “It’s a hard thing to do, but if we could get 10 percent of parents to ask that question, we could start changing the way people view the responsibility of owning a gun.”

Turn in Guns

Anonymous gun buyback programs have been overwhelmingly popular throughout the country. In summer 2016, a gun buyback program in Minneapolis offered Visa gift cards for those turning in guns and had to shut down nearly six hours early due to overwhelming demand. But these programs can be open to criticism, as there is little research to prove their effectiveness.

Regardless, says SPH Dean John Finnegan, encouraging gun buyback programs “could be a great option to get guns off the streets.”

Influence Policy

A number of organizations are currently focusing their efforts on policies that help prevent gun violence, such as requiring background checks for people buying guns, 40 percent of which are purchased in the U.S. without a background check; creating gun violence protection orders so family members and police can get firearms out of the hands of people with signs of dangerous mental illness; and prohibiting those on the No-Fly List from being able to purchase guns.

“Get educated about your state and national officials,” says Nord Bence. “Find out where they stand on these issues and connect with them.”

This article is from the fall 2016 issue of Advances, the alumni magazine of the School of Public Health. See the entire issue on Issuu.