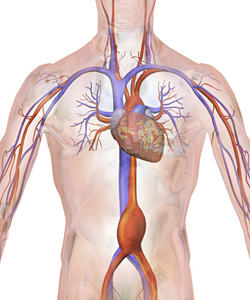

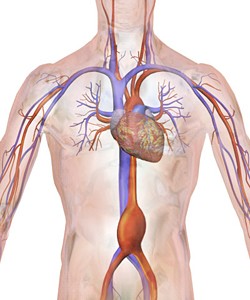

Each year, more than 10,000 Americans die unexpectedly from rapid internal bleeding triggered by ruptured aortic artery aneurysms. The most common type of aneurysm is the abdominal aortic aneurysm, which lurks where the heart’s aorta artery threads through the belly.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are up to 85-percent fatal and doctors have long wished for a way to diagnose them early.

“It’s a big public health problem,” says School of Public Health epidemiologist Weihong Tang. “AAAs are found in young and middle-aged people and affect up to two percent of Americans who are 65 years or older.”

In a study recently published in Circulation, Tang and her colleagues Aaron Folsom, Lu Yao, Alvaro Alonso, Pamela Lutsey, Emil Missov, Frank Lederle, and Christie Ballantyne confirmed the existence of six molecules and proteins in the blood that precede or coincide with the development of AAAs.

Researchers call these disease-linked blood substances “biomarkers,” and in the case of AAAs, the six that Tang and colleagues linked to the condition could one day be included in a test to predict someone’s risk of developing one. Identifying the biomarkers might also be helpful in improving our understanding of AAA formation, aiding in its diagnosis or prognosis assessment, or possibly identifying treatment targets.

Weakening walls

AAAs begin as imperceptible structural imperfections in the aortic artery.

“The wall of the aorta becomes weaker and weaker and thinner until it forms an aneurysm,” says Tang.

Often, there are no symptoms until it ruptures and death from rapid internal bleeding comes swiftly without immediate medical intervention.

The biomarkers they studied are substances known to be associated with inflammation (high sensitivity C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, fibrinogen), thrombin generation (D-dimer), increased cardiac pressure and stiffness (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide), and cardiac injury (troponin T).

To find out if the biomarkers are related to AAAs, Tang and colleagues partnered with the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study that’s been tracking approximately 16,000 people for nearly 30 years. ARIC is a study investigating cardiovascular diseases, such as heart attacks and strokes, but also AAAs.

They wanted to see who in the study had developed AAAs and if the biomarkers in their blood showed any suspicious trends leading to their development.

To do so, the researchers looked at old blood samples of ARIC participants — some of whom later went on to develop AAAs — and compared their biomarker levels.

They also identified the patients who did eventually develop AAAs by examining hospital and death records, and by performing abdominal ultrasound scans on participants to search for undiagnosed AAAs.

Overall, a total of 661 AAA cases were found — 74 of them through the study’s ultrasounds.

When the researchers put all the data together, they discovered that the more of each type of biomarker a person had at a high level, the more likely they were to have developed a AAA. In fact, anyone with high levels of all six biomarkers had a 10-fold risk of developing the condition compared to those who had these six biomarkers at intermediate or low levels.

Knowing what kinds of biomarkers are involved in AAAs gives researchers hints to the pathological pathways that create them. In the future, that could lead to targeted treatments and even ways to prevent them from ever forming.