A new research collaboration between University of Minnesota School of Public Health (SPH) assistant professor Jon Oliver and College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) assistant professor Peter Larsen started in an unlikely place: a parking garage.

“We bumped into each other in the parking garage and started talking about a variety of tick-related projects,” Larsen recalls. A biologist by training, Larsen’s recent work has focused on taking lab-based technologies into the field to capture real-time diagnostics. Oliver is a public health entomologist who focuses on ticks and their role in spreading vector-borne diseases. “Our backgrounds really just dovetail together and this study is an outgrowth of that,” Larsen says.

That chance meeting has now turned into a $3.4 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that seeks to transform our understanding of the transmission of Lyme disease and other tick-borne pathogens. A key goal of the research project is to improve the ability to detect diseases that circulate in ticks and rodents that are often missed by current testing methods, Oliver says.

“There are many diseases in circulation in ticks and rodents, but the way surveillance is currently done, it only captures the specific pathogens and diseases that you’re targeting,” Oliver says. “Using traditional methods, for example, you catch a tick and test it for Lyme disease, but all the other pathogens that may be in that tick are missed. A goal of this project is a faster, more mobile testing technology, but also one that can detect a wider array of pathogens.”

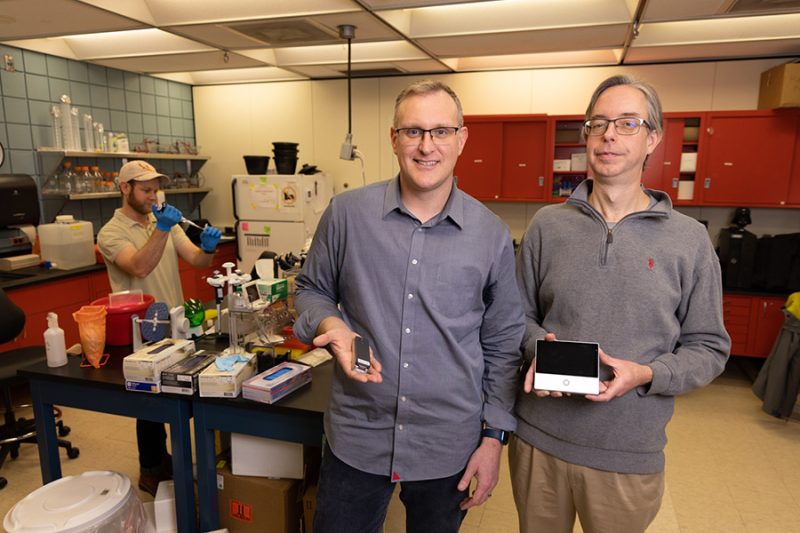

Oliver and Larsen, who are co-principal investigators on the project, said the research puts the U of M at the forefront of new, vector-borne disease surveillance technologies. While traditional testing methods can take weeks or months to return results, Oliver and Larsen’s field-deployable technologies will be able to rapidly assess pathogen infection in rodents and ticks within days or, in some cases, hours.

“The sequencer we’ll be using in the field is the size of a candy bar; you can hold it in the palm of your hand,” Larsen observes. “This whole project is really on the bleeding edge of technology. We believe this is the next generation of pathogen surveillance and discovery.”

The researchers noted several other advantages afforded by the new mobile technology, including:

- The ability to rapidly adjust goals. If the researchers encounter an unexpected virus in the field, they can pivot, adjusting their methods to collect rodents and ticks associated with the just-found pathogen.

- Using real-time data to draw maps and identify hot spots where certain pathogens are concentrated.

- In addition to being portable and simpler than lab-based sequencing machines, the technology is more affordable. As they become available in the future, smaller organizations like county health departments could purchase them to test local rodent and tick populations.

Oliver and Larsen chose Kansas for the study’s field tests because it is one of two places worldwide — the other is in Central Asia — that previous studies have identified as likely places where new pathogens might emerge. This is due to Kansas’ unique ecology and large, diverse rodent community.

College of Veterinary Medicine PhD candidates Evan Kipp and Ben Khoo also contributed to the NIH proposal. Collaborators on the study include the U of M Department of Entomology, the Metropolitan Mosquito Control District, the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Minnesota, and the U of M Raptor Center.

Results of the study will be shared in academic journals throughout the course of the research, as well as through presentations at national and international conferences.